OK, SO MAYBE SPEED DOESN’T KILL, BUT IT SURE CAN HURT!

HALF DAY COURSE REVIEW

Request an introductory course review. No charge for this introductory first site visit.

Green Speed, That Is

From the May 2007 ‘On Course Magazine’ for the Midwest Association of Golf Course Superintendents

It is not difficult to understand our collective fondness for old-time, “classic” golf courses. Part of this is simply a comfort level associated with any familiar presence. Another aspect of our appreciation of older courses is the suspicion that, due to the absence of heavy earth-moving equipment and motorized golf carts, their designs are inherently more imaginative than their modern counterparts.

(The phenomenon does not apply only to golf courses: Asked to choose, sight unseen, between comparably sized houses – one built a hundred years ago, the other just completed – respondents in a recent survey overwhelmingly picked the older house. Typical of the reasons cited for the choice were that it was likely to be better built and have “more character.”)

Golf course architects often acknowledge this attraction to classical features by including pot bunkers, saw-toothed bunkers and other throwback elements in their otherwise modern designs. But while “classic” seems by definition a good thing, not all the individual features loosely associated with the term are desirable in the context of the way golf is played today. An especially bad fit is in trying to combine the more drastic contours of old-style greens with the much-faster putting speeds we have come to expect.

I say “especially bad” because the problem is so prevalent. In fact, in my 20-plus years as a practicing golf course architect, I estimate that seven out of 10 courses I have had the good fortune to play, visit, or consult for have shown some symptoms of this contour-versus-speed syndrome. Sometimes the problem is confined to a single putting surface; sometimes it is evident in a half-dozen cases.

The complexity and severity of the dilemma also vary widely, but its nature is fundamentally the same: The greens no longer “work” because their precipitous slopes were never intended to be combined with today’s “normal” green speeds of roughly 10, sometimes more, on the Stimpmeter.

You would anticipate this problem in the case of a course built at the turn of the 20th century but – given the tendency in recent years to equate pure speed on the greens with “quality” – but it also rears its head at much younger courses, a kind of unintended consequence: In the face of exponential improvements in agronomy and mowing equipment, maintaining the integrity of the playing experience has in this respect become more difficult.

Thus, many green complexes once were cut to heights and otherwise maintained to generate speeds on the Stimpmeter – invented in the early 1900s and in increasingly wide use ever since – of six to eight. Today, many superintendents find themselves in a bind between hewing to that standard and acceding to customer preferences – members in the case of private clubs, patrons at resorts and other public facilities. Striking a harmonious balance is impossible without some sort of remedial action.

Instead, many club managers and green committee chairmen reluctantly – and erroneously — conclude that the best solution is just to tolerate a few bad greens. In rare instances this may be true; in many more situations, however, this conclusion is based on misperceptions concerning what fixing the contour-versus-speed problem would entail, including:

a. The construction will cause significant disruption in play.

b. Remodeled greens will differ from unaltered ones in their receptivity to approach shots.

c. Putting speeds will be substantially different on the “new” greens compared to the old ones.

d. Greens that have been remodeled will require extensive new maintenance practices.

e. The original architect’s design intent will be lost in the remodeling.

f. Remodeled greens will look incongruous in relation to existing ones.

Though these apprehensions sound logical and may have a grain of truth, my view is that they range from exaggerated to downright false. In short, a well-conceived remodeling project is virtually certain to be the superior answer.

For starters, the correct redesign and construction methodology will complete the green remodeling process in 10 days or less, while the grow-in time needed for the sod to re-root and “take” may be as little as 7 to 10 days. True, a temporary green must be used during this interval, but it’s much shorter than most people anticipate and well worth the trade-off.

What’s more, a discerning design and construction strategy will in due time ensure that the remodeled green receives incoming shots and putts like the other greens on the course — but now with contours in synch with the desired green speed. One such successful strategy is to use the course’s existing topdressing and Greensmix in the new “tested” Greensmix that will perform to USGA Green Section Specifications. The use of a USGA-approved soils testing laboratory, as we strongly encourage our clients to do, guarantees adherence to these specifications.

This approach contrasts with that advocated by many design and agronomic consultants today, who recommend either using a course’s existing topdressing and Greensmix or completely replacing the Greensmix with new materials prepared off-site.

I would like to add a third option. Reusing the former Greensmix, which in many cases is just old topsoil ‘push – up’ greens, may result in a hard, compacted green surface in the remodeled green if the old mix or topsoil contained a significant amount of fine particles, typically clay, silt, or very fine sand. The resulting question I frequently hear is: “My old ‘push-up’ greens worked before in terms of drainage and how they held a shot, why wouldn’t they work again?”

My response is that the older greens commonly developed small soil fractures and fissures over time, which in turn helped minimize compaction and allowed proper infiltration and percolation to occur. This would be lost over the first several years after remodeling in the remodeled greens, as the replacement of the existing mix would compact to a higher degree. It will take time and some significant aeration and aggressive topdressing practices to reduce this compaction and regain the deep soil fractures and fissures that were once present. If you can put up with the compaction for the first several years after the remodeling while educating members or public play then this is a viable option.

Another proposed solution I regularly hear — to just replace the old Greensmix with new USGA approved Greensmix. This option leads to remodeled greens that receive incoming shots and putt much differently than the layout’s unaltered greens. This tack may also require dramatically different maintenance practices relative to original unaltered greens.

I often tell superintendents to avoid this option unless they commit to a long term remodeling program which entails new USGA Greensmix being incorporated into all the remaining greens over no less then a 3 year time frame. If you can put up with greens that vary in how they putt and receive incoming shots for approximately 3 years after the initial remodeling begins while educating members or public play then this is a viable option. I am sad to report that many superintendents often find that members or public golfers significantly complain about the difference in the new green’s playability compared to the old unaltered greens during this time frame.

My company utilizes both methodologies described above and at times utilize a hybrid of the two. We also believe in off-site mixing using new Greensmix but while using a portion of the existing Greensmix in this new Greensmix being prepared. The new Greensmix must meet USGA Green Section Specifications by an approved soils testing laboratory in terms of overall testing requirements. Accordingly, the newly remodeled green(s) may not receive shots and putt exactly the same as other, unaltered greens. But they will much more closely approximate the receptivity and putting characteristics than would be the case using the two other strategies. And our experience confirms that the nominal expense and effort require to implement this hybridized methodology pays off in enhancing the golf experience. The problem with this methodology is that it will only work when remodeling portions of a few greens and you will need a source to start with i.e. a portion of a practice putting green or nursery green to borrow old Greensmix from to gather and transport off site to the company doing the mixing.

We also suggest recycling sod from the existing green and collar, where possible, to promote continuity between the old green and the remodeled edition. In cases where the remodeled green is larger then the former existing green, we advocate using sod from the collar for the green’s expansion, then gradually bringing down the height of this sod over time to the green’s mowing height. We recommend using this collar height sod in the back of the green while the existing green sod from the back of the green can be used in the remodeled area. This methodology minimizes player disturbance as most players are short, left, or right in their approaches to a green versus long. Sod for the collar can then come from existing turf at the beginning of the fairway, then incrementally brought down in mowing height to that of the existing unaltered collar grass.

Naturally, special attention to maintenance issues is required initially to nurture newly planted or transplanted turf. Nonetheless, a comprehensive approach to the remodeling process will produce remodeled greens that soon blend in – esthetically and in terms of the maintenance they demand – with the course’s other green complexes.

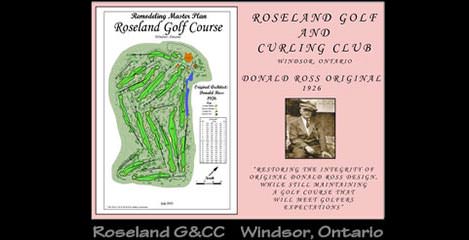

Always more debatable than purely agronomic issues is the question of adulterating or compromising the original architect’s design intent. A perfectly legitimate concern, it inevitably leads to other questions: How important is this really to the membership or the regular patrons at the course being considered? Does the original designer enjoy a reputation that, in its own right, makes his work worth preserving? Can his perceived design intent be reconciled with the game’s modern-day evolution and the course’s overall goals?

An object lesson from our portfolio involving an anonymous private club in the eastern U.S. helps elucidate the delicate balance for which to strive. Designed by the legendary Willie Park, its heritage is beyond dispute. Still, with 27,000 rounds per year, the superintendent was struggling to maintain healthy turf conditions, particularly on a par 3 green where 70 percent of the 5,000-square-foot putting surface had grades of four to eight percent, sometimes more, while the remaining 30 percent had more comfortable contours of one to four percent. Similar proportions existed on four other greens and, as the superintendent was required to maintain putting speeds of 11 to 12, these were places where any three-putt was deemed a good effort.

The superintendent reasoned that a putting surface with at least 4,500 square feet of additional surface in the one-to-four-percent-slope range would present a much more reasonable and fair test of golf, not to mention maintenance. The membership’s concern was that Park’s “false front” of five-plus percent – a trademark design element in these particular original designs and the overall challenge of the green– would be lost in the redesign.

My company’s redesign included an increase to 5,800 square feet in overall green surface — an additional 800 square feet, in other words. The new surface area maintained a gentler but still visually apparent and challenging “false front” on a four-to-seven-percent grade, while 4,500 square feet of the green now exhibits an interesting variety of one- to four-percent contours with modified but still preserved challenge in the three to four percent range. The superintendent gained 3,000 square feet of new “cupping” area to more evenly distribute play and related wear and tear. For their part, the membership was happy to see the additional one to four percent cupping areas of the remodeled green while the “false front” to the green and the overall challenge was still preserved.

Granted, from a purely mathematical standpoint 6,500 square feet might have made more sense given the 27,000-round volume on the course. However, Park’s greens, apropos of their era, are generally small, and 6,500 square feet would have constituted the proverbial “sore thumb.” Putting surfaces on the course’s other par 3s average 5,000 square feet – a dimension at which the superintendent was able to maintain top-quality conditioning of the bent/poa greens.

“Will the remodeled green look out of place?” An excellent question, one that goes to the heart of the golf course architect’s design philosophy, appreciation of the game’s history and traditions, and critical judgment. For every sensitive interpretation of an original designer’s concepts, there is, regrettably, an atrocity – the equivalent of a red crayon stripe across a classical canvas, often made in the name of “progress” but conspicuous in its affront to context.

Thus choosing a golf course architect with significant classical design restoration experience is a must in order to maximize the potential to harmoniously blend the classical look of the restored, renovated, or remodeled green to that of the other existing classical green complexes that have remained unaltered.

On the opposite side of the ledger is blind obeisance to the original architect’s drawings and exact specifications, some of which may be impossible or undesirable to preserve. Classical design elements are generally worth maintaining, but in a few cases existing green design is of poor quality and does not possess any attributes that warrant restoring. Golden Age golf course architects had bad days, too, after all.

Fortunately, modern design software and its three-dimensional display capabilities allows architects and clients alike to make informed choices about putting speeds, contours, what to keep, what to tweak.

In closing, don’t hold on to greens that don’t “work” with your current putting speeds. Creative and carefully conceived redesign, coupled with a prudent and timely construction methodology, will yield the desired results with minimal disruption to play, as well as lowest-possible cost and emotional travail.

To revert to the aforementioned residential housing analogy, you may prefer the 100-year-old house, but that doesn’t mean you will be foregoing central heat and air conditioning. Faster putting speeds have generally added intrigue to the already-intriguing game of golf, and this seems unlikely to change any time soon unfortunately. Neither will our devotion to the game’s history. A reasonable synthesis of the two is achievable as long as we watch our slopes and speeds.

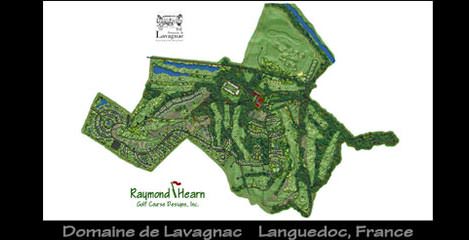

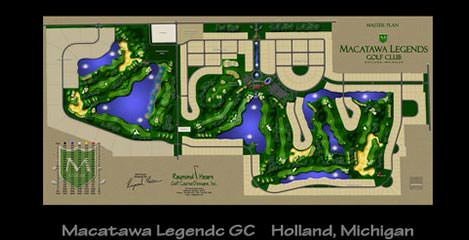

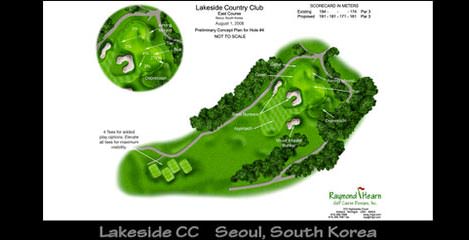

The author, Raymond Hearn, is a member of the American Society of Golf Course Architects and also heads the firm of Raymond Hearn Golf Course Designs (www.rhgd.com) located in Holland, Michigan.