Is the Tree Program Working for Your Club?

As Henry Beard observed in “Mulligan’s Laws”: “You can hit a 200-acre fairway 10 percent of the time and a two-inch branch 90 percent of the time.”

Golfers may grin in validation of his calculus, but it also suggests the ambivalence of trees in golf course architecture. On the one hand, trees are unquestionably among the most visually appealing features of many parkland courses found throughout the Great Lakes Region and elsewhere. Beard’s quip also captures the tree’s uncanny intrigue as a properly deployed design element.

But trees can also be problematic for the strategic integrity of a given hole; and because unlike, say, bunkers, trees are not static entities, their rapid growth can compromise a well-conceived original design. What’s more, the very grandeur that prompts us to value trees can adversely affect maintenance of turfgrass, especially on tees, fairways and greens.

Equilibrium in a course’s tree program is possible, however, and what follows is an object lesson in the problems typically found on many golf courses I have consulted with. The fictitious name of the otherwise anonymous course provides a clue to the success of their old approach.

Case Study: BAD TREE COUNTRY CLUB

Purists argue that it is doubtful that trees even have a place in terms of a course’s strategy considering their vulnerability to storms, disease, or other forms of instantaneous elimination. This is a debate relegated to academia and/or the taproom by the actual state of affairs at many courses I have visited, including Bad Tree.

In consulting there — a very prominent property in the Great Lakes Region — I was flabbergasted by the negative effect the tree program, or absence of one, had on this classic layout, whose design dates to the early 1900s. After studying the club’s early aerial photographs, it was apparent that the golf course architect specifically intended for certain trees to influence the layout, playability, and strategy in a certain and limited way. In round numbers, this meant only about 300 specimens in the entire layout, which occupies roughly 175 acres.

As frequently happens, an esteemed member with the best of intentions decided to start a tree planting campaign in the mid 1960s. This continued in the years follow, all without involvement of a professional golf course architect. The result, needless to say, was a lot of trees, the placement of which often seemed random, devoid of planning for future consequences.

During my first visit I asked the greens committee chairman if the club knew how many trees where currently on the golf course. He responded that he did not know but indicated that the committee was aware of the existing tree program’s downside: This wonderful, formerly spacious design had wrongfully evolved into a tight course with fairways framed by huge tree canopies.

Again, the image is not unappealing in itself; but, sadly, the damage to the golf experience is immense. Even as the committee acknowledged the problem they were reluctant to have any of the trees removed. And my 20 years of practice suggest the prevalence of this attitude is roughly equal – 90 percent – to whacking that two-inch tree between you and the green. It is very difficult for club officials to give the green light to remove a tree that Jane Doe donated to the club, in memory of John, years ago.

It is implausible to ignore such sentiments in devising a tree program, so a little creativity is required. Acknowledge members’ contributions in the tree department via a substitute memento, perhaps a plaque in the grillroom, a bench on the course, that sort of thing — a simultaneous nod to the traditions of the club and the benefits of at least some change.

My consultation at Bad Tree also duplicated a scenario common among previous clients, that is, failure to correctly prioritize the tree program, which they viewed as incidental to a comprehensive renovation involving new or revamped teeing grounds, bunkers, cart paths, drainage, the works. I conceded that these items needed attention, but insisted that their tree problem needed immediate action, pointing out that it had implications for all other design options being contemplated.

Shortcomings in the layout specifically related to trees included diminished playability. For example, impinging tree lines made using a driver off many tees – even ones where the hole’s yardage indicated it ought to be a necessity – a foolish choice, as the fairways were undulating and pitched toward the woods. The problem was exacerbated by landing areas seemingly apportioned for PGA Tour pros – 100-140 feet (tree line to tree line), in many instances.

The flip side is enhanced “playability” in ways that the architect of record plainly did not envision. Dogleg fairways are usually circumscribed by trees where such fauna exist. For better or worse, advances in club and ball technology, and therefore ball flight, have fundamentally altered the proportions of these older dogleg configurations. Whereas they once rewarded the shaping of shots around trees, modern shot trajectories simply fly the tree and the corner of the dogleg, often at the tee shot’s zenith. The tree can be returned to the strategic equation by juggling other proportions of the design. Moving the tees back is the most obvious one, naturally, but there are other tactics available. Narrowing the fairway opposite the dogleg with a hazard, to name one, can encourage players to try to cut the dogleg, while making it the low-percentage play.

Still, while the obsolete dogleg tree is, in effect, too small, too big is a much more ubiquitous problem in tree programs. Because of overgrown trees at Bad Tree, as little as one-third of the total square-footage of most tees was effectively usable. In come cases, overhanging trees dictated club selection and ball flight, even on longer holes – OK for those of us proficient in hitting that “stinger” 2-iron, not so good for the rest of us. The difficulty was compounded by generally inadequate “bail-out” areas for missed tee shots.

This problem’s obnoxious cousin is a canopy substantial enough to block of a significant portion of the green from all but a discreet area of the fairway, in turn demanding not just a shaped shot but a “tricked up” slice or hook. From the sublime to the ridiculous, this situation existed in 11 iterations at Bad Tree.

Marginal tree programs even have non-playing victims. A round with the greens committee chairman at Bad Tree included a conversation with two gentlemen who had evidently spent a good deal of the day searching for and playing balls in the woods. They complained about poor turf conditions in the dense forest, concluding that the club “needed to find a superintendent who could grow grass.” I felt compelled to respond that the most talented superintendent in America could not possibly grow healthy turf in these areas with virtually no sunlight. Even the bulging tree roots pointed to the lack of water and nutrients; worse, the same phenomenon was at work on numerous tees and fairways.

Most disheartening, though, was when extolled the shot-making challenge of tree canopy between fairway bunker and the green, thus largely eliminating the possibility of extricating oneself from difficulty with a quality bunker shot.

Such “double jeopardy” golf predicaments, I tried to explain diplomatically, were thought to be axiomatically unfair and undesirable among right-thinking golf course architects.

It goes without saying that the older your course, the more likely it is to be beset with the above difficulties, but my hunch is that one of them will resonate with most readers. In summary, you can assess the urgency a professional evaluation of your tree program by considering the existence and severity of the following;

- The original design intent has been compromised by the trees currently on the course.

- The trees are eliminating or greatly reducing the use of the driver as a viable club selection on certain tees.

- Only one side of many tees is being overused because of tree canopies ahead of the tee.

- Certain tree canopies fronting fairway bunkers have grown large enough to make standard, direct shots to the green (or second landing areas on par 5’s) impractical if not impossible.

- Approaches to greens are too restricted due to adjacent trees or parts thereof

- Turf quality is being jeopardized by limited sunlight and lack of water, air and nutrients.

- There are more trees on the golf course than grains of sand in your bunkers and the golf experience feels claustrophobic.

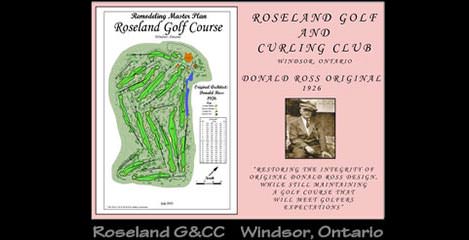

As a member of the American Society of Golf Course Architects with an extensive track record in remodeling, renovation, and restoration, I recommend that you retain a golf course architect to review your current tree program. His or her expertise aside, the collaboration is invaluable in defusing intra-club tensions about how to achieve the mutually agreed-upon goal: the best course possible.

Devising the appropriate tree plan shouldn’t be harder than, say, hitting that 200-acre fairway – so, yes, it will almost always generate controversy. But like the one you stripe down the middle, it will feel really good.

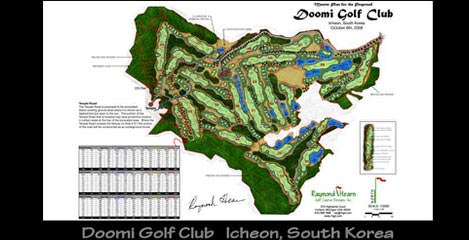

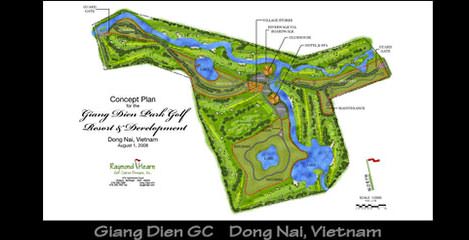

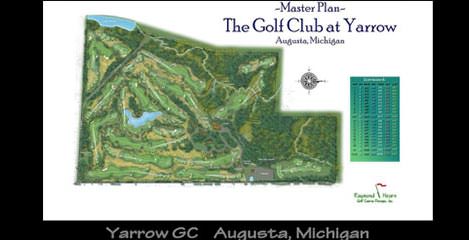

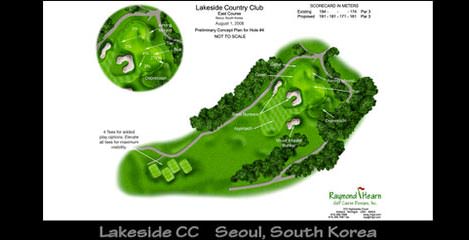

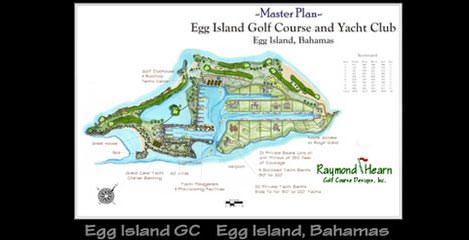

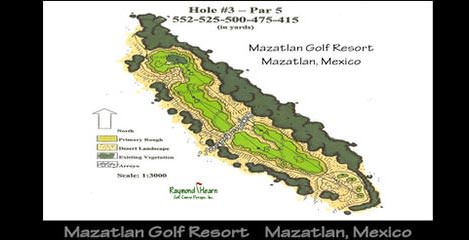

The author, Raymond Hearn, is a member of the American Society of Golf Course Architects and also heads the firm of Raymond Hearn Golf Course Designs (www.rhgd.com) located in Holland, Michigan.

HALF DAY COURSE REVIEW

Request an introductory course review. No charge for this introductory first site visit.